Writing

Interactive Stories in the Classroom

Duane

Szafron, University of Alberta

Mike

Carbonaro, University of Alberta

Maria

Cutumisu, University of Alberta

Stephanie

Gillis, Holy Trinity High School

Matthew

McNaughton, University of Alberta

Curtis

Onuczko,, University of Alberta

Thomas

Roy, University of Alberta

Jonathan

Schaeffer, University of Alberta

Abstract

The last five years

have seen interactive storywriting technology mature to the point where it has

become widely popular and is starting to be recognized as a new communications

medium. The two most common examples of interactive stories are computer games

and educational training simulations. Non-linear interactive stories involve

the reader as an active participant in the story where the player (reader) has

a direct influence on the plot of the story. Compared to traditional linear pen-and-paper

(or word processor-created) stories, interactive stories come with a new set

of challenges, but also provide an interesting set of opportunities. Currently,

students are not exposed to the challenges or opportunities of writing interactive

stories for two reasons. First, interactive storywriting technology is too complex

to be used in the classroom. Second, critical parts of this new technology require

the writer to construct sophisticated computer programs to tell the story. In

this paper, we describe how we have solved these two problems by developing a

student-friendly environment (ScriptEase) that enables non-programmers to write

interactive stories using a simple set of tools. Specifically we describe how

High School students used our tools to create Computer Role Playing Game (CRPG)

stories that can be played (read) as adventures in the popular Neverwinter Nights

computer game.

1. Introduction

An interactive story consists

of several non-traditional elements including sound, graphical characters,

and an interactive storyline in which the "reader" participates as

a player character (PC) in the story. This participation allows the "reader" to

make choices that determine the story line. The last five years have seen interactive

storywriting technology mature to the point where it has become widely popular.

Unfortunately this technology requires the writer to also write sophisticated

computer programs to control the interactions between the game components.

For example, when the "player" steps on a particular stone in a corridor,

scripting code must be written to recognize that the stone has been stepped

on and to trigger an appropriate trap. Writing scripts to control this level

of detail in a story is very burdensome to the writer. The goal of our research

is to create an environment that enables non-programmers to write interactive

stories without providing scripts to control this level of detail. To reduce

the scale of the problem to a manageable level, we decided to focus on computer

role playing games (CRPGs). In our project, interactive stories are "written" by

creating game adventures for the Neverwinter Nights (NWN) computer game system.

NWN is a multi-award winning (86 awards) CRPG from BioWare Corp. Stories are "read" by

playing them as NWN adventures.

![]() An

external link to Neverwinter Nights. http://nwn.bioware.com/players/

An

external link to Neverwinter Nights. http://nwn.bioware.com/players/

![]() An

external link to BioWare Corp. http://nwn.bioware.com/

An

external link to BioWare Corp. http://nwn.bioware.com/

Although game play can be used as an educational experience, we are more interested in game design than game play (McFarlane et al. 2002). This is a relatively new endeavor (Robertson & Good, 2005). The focus of the research described in this paper is to use interactive storywriting as a new vehicle for creative expression. In a traditional story, the world is created with words, using descriptive prose, and the story is told with words, through narrative prose. In an interactive story, the world is "painted" with a computer-aided design tool and the story is told dynamically as the PC navigates through the world. BioWare provides the Aurora toolset along with the NWN game system, so that amateur writers (including students) can paint the background for their stories. There are three potential benefits of interactive storywriting. First, students can improve the skills necessary to effectively use an increasingly important communications medium. Second, they will learn important logical thinking skills, similar to computer programming, but in an environment that does not have the stigma of computer programming. Third, this new communications medium provides an alternative mechanism for creative expression that may allow students to improve their expressive skills.

The structure of this paper mirrors the student experience. Student writers begin by completing a tutorial that teaches them how to play (read) a story using NWN. Students then complete a second tutorial that teaches them how to use the Aurora Toolset. They use it to create the setting, props, non-player characters (NPCs) and dialogs for their story. The paper then describes one of the main stumbling blocks that can prevent a writer from creating an interactive story - the necessity of writing computer program scripts to control the interactions in the story. We describe our novel solution to the problem, which we call generative patterns, and our tool, ScriptEase (2005), that allows writers to generate scripts from patterns without programming. Finally, we describe feedback we received from the teacher after piloting our storywriting software in a class of grade 10 English students.

2. Game Playing and Creation Using

NWN Tools

The NWN game contains an

engine that renders the graphical objects and characters, manages sound and

motion, and dispatches game events to scripts. This game engine is designed

to play stories composed of individual modules constructed by game designers

(storywriters). A module contains areas (map sections), NPCs and other game

objects (props) that can be scripted to respond to game events using the NWScript

language.

The game comes with a story that contains seven modules. Recently, expansion packs for two more stories have been released. However, NWN is a community-based game. Thousands of people write stories and post them on the web for others to enjoy. For example, Neverwinter Vault hosts more than 4,100 adventures. The most popular community adventure has been downloaded more than 250,000 times and the tenth most popular has been downloaded more than 87,000 times, as of March 2005.

For the students to play the Neverwinter Nights game and to develop the backgrounds for their own stories, we developed two tutorials based on the existing BioWare tools. The tutorials were developed by a high school teacher and tested by high school students before our pilot project was conducted.

![]() An

external link to Neverwinter Vault. http://nwvault.ign.com/

An

external link to Neverwinter Vault. http://nwvault.ign.com/

2.1 Playing the Game

The first tutorial helps

the student to navigate a PC through the prolog of the NWN story that comes

with the game, learning the controls and making choices about where the PC

should go, what the PC should do and what the PC should say. The Video clip

shows the actions of a PC at the start of the Prelude. It shows the PC interacting

with two NPCs, Pavel and his brother Bim. When the PC meets Bim, the user is

offered a short "in-game" tutorial on adventuring that describes

many of the controls that the player can use to manipulate the PC. The video

clip shows only the first 30 seconds of play for the Prelude, with some of

the conversation with Pavel omitted for brevity. In our experience it takes

high school students from 2 to 3 hours to play through the Prelude and gain

a basic understanding of the game.

![]() Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~160 KB) Tutorial on playing NWN to help the student to navigate

a PC through the prolog of the NWN story that comes with the game, learning

the controls and making choices about where the PC should go, what the PC should

do and what the PC should say.

Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~160 KB) Tutorial on playing NWN to help the student to navigate

a PC through the prolog of the NWN story that comes with the game, learning

the controls and making choices about where the PC should go, what the PC should

do and what the PC should say.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, 400x300 pixels, ~13 MB): An excerpt of the first 30 seconds

of the play from the NWN prelude.

Video

clip (QuickTime, 400x300 pixels, ~13 MB): An excerpt of the first 30 seconds

of the play from the NWN prelude.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, 800x600 pixels, ~150 MB)

Video

clip (QuickTime, 800x600 pixels, ~150 MB)

2.2 Creating the Story World

The second tutorial helps

students to create the "areas" that form the backdrop of their stories

and to populate each area with a collection of props and NPCs that the PC can

interact with as the protagonist of the story. In the tutorial, there are two

areas, the outside of a castle (Exterior) and the interior (Castle). The castle

is divided into rooms and the students use the Aurora toolset to populate the

rooms with appropriate props and NPCs. The Video clip shows how a statue is

created and placed in a room of the castle. First an existing statue is selected

to use as a model. Then a copy of the statue is created so that it can be edited.

The "Usable" checkbox is selected so that the PC can interact with

the statue (when the user clicks on it). The "Has Inventory" checkbox

is selected so that the statue can have items hidden in it. The designer drags

a book called the "Origins of Magic" from the "Custom Items" palette

to the "Contents" palette to place a copy of the book in the statue.

Later in this paper, we will see how the story is "scripted" so that

when the PC takes this book out of the statue, a locked door is unlocked and

opened. The Aurora toolset tutorial shows how to create many other kinds of

placeables (props), such as tables, chairs and chests, and how to place them

in the virtual world. It also shows how to create and paint doors and triggers.

A trigger is an area on the floor that is activated when a character walks

on it. There are several kinds of triggers including traps and area transitions,

which transport a character from one area of the virtual world to another.

The tutorial also shows how to create items, such as books, clothing and jewelry

that can be carried and used by creatures. Finally, the tutorial also shows

how to create non-player characters (NPCs) and how to write dialogs that the

PC can have with various NPCs.

![]() Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~500 KB) The second tutorial on using the Aurora Toolset

to helps students to create the "areas" that form the backdrop

of their stories and to populate each area with a collection of props and

NPCs.

Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~500 KB) The second tutorial on using the Aurora Toolset

to helps students to create the "areas" that form the backdrop

of their stories and to populate each area with a collection of props and

NPCs.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, ~63 MB): Using the Aurora Toolset to create a statue that

contains a book.

Video

clip (QuickTime, ~63 MB): Using the Aurora Toolset to create a statue that

contains a book.

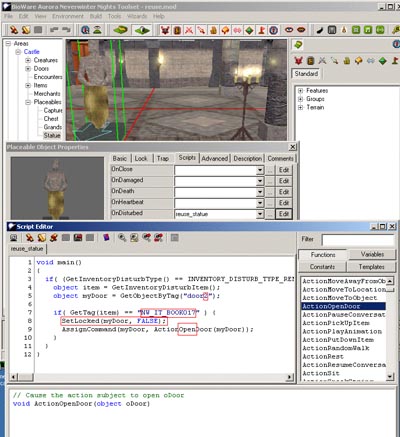

3. Problems with Manual Scripting

In addition to world and

object layout, the Aurora toolset can also be used to attach scripts to objects.

An object is selected and a script is entered using a C-like programming language

called NWScript. Essentially, an event handler can be scripted for any of the

events to which the object can respond. For example, when a specific item (such

as the "Origins of Magic" book) in a specific container (such as

a statue) is disturbed (removed), the writer may want a nearby door to be unlocked

and opened. However, since most amateur and student writers are not programmers,

they find scripting very difficult. Amateur writers often try to copy-and-paste

scripts from existing stories without understanding the code. For example,

Figure 1 shows some hand-written scripting code that closes a door when a specific

item (a sword) is taken out of a container (a chest).

Figure

1.Scripting code that closes a door when a sword is removed from a

chest.

![]() Full

size image

Full

size image

To re-use this scripting code for the statue and book, it could be copied from the OnDisturbed event of the chest and pasted into the OnDisturbed event of the statue. However, several changes would need to be made to the code to "adapt" it properly, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure

2.Modified scripting code that unlocks a door when a book is removed

from a statue.

![]() Full

size image

Full

size image

First, the tags door1 and UA_SWORD were changed to door2 and NW_IT_BOOK017. Second, the code to close the door was changed to code that opens the door, by replacing the line AssignCommand(myDoor, ActionCloseDoor(myDoor)) by the line AssignCommand(myDoor, ActionOpenDoor(myDoor)). However, the writer must also figure out how to unlock the door, before opening it and there is no obvious way to do it. Perhaps the command is AssignCommand(myDoor, ActionUnlockDoor(myDoor)). In fact, this will not work and the correct command is: SetLocked(myDoor, FALSE). Most non-programmers would have difficulty figuring out what to change and how to change it. There are web forums on the BioWare site, where writers ask other amateur writers who know how to program to write individual scripts for them. However, these forums are not a good substitute for writers being able to generate the scripting code for themselves.

![]() An

external link to the Neverwinter forums at BioWare. http://nwn.bioware.com/forums/viewforum.html?forum=47

An

external link to the Neverwinter forums at BioWare. http://nwn.bioware.com/forums/viewforum.html?forum=47

A commercial or amateur (non-student) CRPG story is comparable in scope to a novel and can contain thousands of NPCs and other game objects that must be scripted. An interesting short story, written by a high school student can contain anywhere from five to one hundred scripted NPCs and other scripted game objects. Although there is a difference in scale between a novel-sized story and a short story, the four manual scripting problems encountered by the storywriter are the same:

4. Patterns - A Solution to Writing

Scripts

Our solution to the problems

of scripting in interactive storywriting is embodied in a new tool called ScriptEase.

ScriptEase uses patterns that generate scripting code automatically. A storywriting

pattern is a reusable device that encapsulates a common storywriting theme

or idiom. An example of a large-scale theme is a hero who must perform several

quests before reaching the climax of the story. This theme is as old as the

labors of Hercules, and we would classify such themes as plot patterns.

If a writer wants to incorporate this theme into an interactive story, scripts

must be written to prevent the PC from moving to the climax without performing

the required quests. A plot pattern that represents this theme would generate

the scripting code automatically. On a smaller scale, the idiom of a door that

is unlocked when the protagonist disturbs an item in a container is common

in the fantasy genre. We represent this idiom using an encounter pattern.

In ScriptEase, this particular encounter pattern is referred to as Container

disturb –(specific item) toggle door. Rather than

forcing the writer to write a script every time this idiom is used, in ScriptEase,

the writer selects the pattern corresponding to this idiom and the scripting

code is generated from the pattern.

![]() An

external link to ScriptEase. http://www.cs.ualberta.ca/%7Escript/scriptease.html

An

external link to ScriptEase. http://www.cs.ualberta.ca/%7Escript/scriptease.html

Our patterns are inspired by software design patterns, but they are different. Design patterns are recurring patterns of software, but our patterns are really storywriting patterns. Each pattern is general enough to be used in many different situations within a story and indeed across many stories. However, this generality comes with a price. A pattern must be adapted for an individual story whenever it is used and adaptation requires some effort.

ScriptEase provides more than fifty encounter patterns that can be adapted for use in thousands of different stories. In fact, there are several kinds of adaptation, each requiring different levels of abstraction skill and, therefore, different levels of cognitive ability. The simplest kind of adaptation only requires the writer to select the options required by a pattern; for example, selecting the container, the item and the door objects for the pattern described previously. The kinds of adaptation in increasing order of difficulty are:

![]() Text-Based

Material (pdf, ~16 KB): Software design patterns.

Text-Based

Material (pdf, ~16 KB): Software design patterns.

In the pilot, the students used a ScriptEase tutorial that describes some of the patterns and shows how to adapt them. The Video clip shows how the ScriptEase tool is used to select encounter patterns, adapt them for a story and generate the scripting code from them. In the first part of the video, the tutorial story module that was created using the Aurora toolset is opened and an instance of the Container disturb -- (specific item) toggle door pattern is created. This instance is adapted by selecting game objects that correspond to the container (the statue), the specific item (the book) and the door (the door) to be unlocked and opened. In the second part of the video, more complex adaptations are illustrated (cognitive levels 2, 3, and 4). The next Video clip shows what happens in the story when a PC encounters a Container open/dead pattern that was one of the most popular patterns used by the students in their stories. In this case, the pattern has been adapted (conceptual level 4) to create a visual effect and spawn a creature when the chest was opened. The creature is an animated suit of armor. The creature would also be spawned if the PC destroyed the container instead of opening it. The container contains a brass key that is needed by the PC to develop the plot of the story.

![]() Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~274 KB) Tutorial on ScriptEase.

Text-Based

Material: (pdf, ~274 KB) Tutorial on ScriptEase.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, ~62 MB): Using ScriptEase to adapt a pattern and generate

scripting code for the statue, book and door.

Video

clip (QuickTime, ~62 MB): Using ScriptEase to adapt a pattern and generate

scripting code for the statue, book and door.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, 400x300 pixels, ~12 MB): A PC encountering a Container open/dead

pattern in a story.

Video

clip (QuickTime, 400x300 pixels, ~12 MB): A PC encountering a Container open/dead

pattern in a story.

![]() Video

clip (QuickTime, 800x600 pixels, ~42 MB)

Video

clip (QuickTime, 800x600 pixels, ~42 MB)

5. The Classroom Experience

A grade 10 English class

used NWN, the Aurora Toolset and ScriptEase to write interactive short stories

as part of their short-story curriculum. The 20 students had just finished

learning how to write traditional short stories in their English class and

the teacher wanted to provide them with a non-traditional learning activity

that was fun. The students participated in a two-day workshop at the University

of Alberta, where they became familiar with NWN, the Aurora Toolset and ScriptEase

by working through the three tutorials described in this paper and by starting

their own interactive story. They worked under the supervision of their teacher

and some teaching assistants who were familiar with the tools and tutorials.

The students then returned to their high school to finish their short stories

during three class periods. The interactive stories were submitted and graded

by their English teacher.

Our goals for this pilot project were:

The feedback we received from the pilot indicates that students have different attitudes towards interactive storywriting and traditional storywriting and that they exhibit different behaviors when performing the two activities. This feedback has resulted in several hypotheses about the differences. In this section, we describe the feedback we obtained along with some preliminary hypotheses we have developed to explain the feedback.

There are many ways to describe, analyze and interpret the feedback we received. Our approach is to begin with an observation from the teacher involved in the project. She stated:

"Never underestimate the importance of fun in learning, since activities where students want to do the work make learning easier and allow students to learn more quickly."

However, fun is such a generic term that finding out whether the students had more fun with the interactive story than the traditional story would not be helpful unless we can quantify the consequences of the "extra" fun. Therefore, to interpret the feedback we asked the teacher and ourselves four informal questions:

We were not surprised to discover that all of the students found that at least parts of interactive storywriting were fun. Although only about a third of the students in the class were interested in writing a second traditional short story, about two thirds of the students wanted to write another interactive story (even if they had to do it at home, outside of school time).

We discovered two differences in the two storywriting modes. One difference is related to getting started and the other difference is related to staying on task. In addition we gathered some other general feedback.

5.1 Getting Started

It is often difficult for

students to start writing a short story and many students complain: "I

don't know where to start". None of the students had problems starting

their interactive story. Why? It is easy to say that students did not have

trouble getting started since starting an interactive story is "fun".

However, to really understand why it was easy to start their story, we must

look at the differences between the process of starting to write a traditional

story and starting to write an interactive story. In other words, we must explain

why starting the interactive story was more fun than starting a traditional

story.

To start a traditional story, it is necessary to set the scene of the story by writing a considerable amount of descriptive prose, before getting to the "good" part of telling the story. With an interactive story, the scene can be quickly "painted" using the Aurora Toolset to add scene components. We hypothesize three main consequences of this difference that we believe make it easier to start an interactive story (and therefore make it more fun).

Time saved during scene set-up provides more time to write the character dialogs that are key to the story itself. It is possible that writing a play instead of a story could have the same effect, but a playwright must still write down a textual description of the stage to replace the description in a story. Setting a scene is just easier to do visually than textually. This is not surprising since at an early age children use toys to set the stage for stories that they want to play. The toys provide the visual background that replaces the tedious scene description necessary in a written story and children quickly focus on the dialog between the toys - the story itself.

5.2 Staying On Task

Many high school students

have difficulty completing tasks that require many hours of work - and a traditional

short story is no exception. Some deviations from task to other learning activities

may provide alternative benefits, but ultimately students must complete a short

story to gain full benefit from the exercise. Few students had difficulty staying

on task while writing their interactive short story and the deviations from

task were usually viewed as beneficial to the outcome of completing the story.

Most students were so engaged that they wanted to work during their lunch breaks

during the workshop. After returning to the school many asked to spend more

time working on their stories outside of class time and a lab at the school

was made available to accommodate their wishes.

Why are students more willing to stay on task when writing an interactive story, or equivalently why is interactive storywriting more engaging, during the middle or end of the storywriting process? Although quick visual feedback is useful in getting started quickly, students can be distracted from any task that is repetitive or does not evolve in difficulty or stimulation level over time. One might think that, for some students, the fact that interactive storywriting is easier at the start could actually increase the boredom factor and make them tire of it more quickly. Based on our experience, we postulate that it is the "interactive" nature of interactive storywriting that most contributes to staying on task. We identified two kinds of interaction that we feel are important. There is interaction between the writer and the tools (already discussed in the Getting Started section) and there is interaction between the writer and the other students.

Interpersonal collaboration was not encouraged or discouraged during the interactive storywriting process. In fact, we did not even think about interpersonal collaboration in designing the activity. What we discovered was that students began collaborating on their stories from the beginning of the tutorial exercises. One student would spontaneously say to the next student, "look what I tried" and the other student would immediately get involved by adapting the idea to his/her own story or by suggesting related things to try. Groups of students began gathering at one workstation or another observing particular students' activities. This encouraged all the students to produce better stories, knowing that their work was being seen/appreciated by their fellow students. Constructive collaboration within a community of learners provided students with an opportunity to improve their critiquing skills. We believe that it also resulted in better understanding of concepts since students would often try to explain things (that they had figured out by themselves or that were clarified by the teacher) to their peers. The teacher contrasted this high level of interpersonal collaboration in interactive storywriting with the collaboration in traditional learning activities:

"ScriptEase created interaction among my students which was not typical of an individual activity such as storywriting. This way of storywriting encouraged collaboration before, during and after their stories were complete."

5.3

Other Feedback

Several other differences

were noted in student behavior, that may or may not be related to the fun

factor, and we have not yet constructed any model to explain them.

There is a current trend in education to integrate technology throughout the curriculum. However, it is a challenge in some disciplines. For English classes, besides the standard approaches of using word processors and slide presentations, there are few opportunities for adding relevant and innovative technology into the curriculum. Interactive storywriting provides a natural opportunity for technology integration.

The use of computer technology to promote critical thinking during problem-solving activities can be an important part of a student's educational experience (Jonassen, 2000). Critical thinking involves being able to think reflectively and effectively and to analytically assess evidence (Santrock, 2001). Various aspects of critical thinking are often associated with the higher-order instructional objectives of application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation as described in Bloom's et al. (1956) taxonomy. Such instructional objectives are well suited to the context of interactive storywriting. Application objectives require having students apply existing knowledge to new situations they encountered during problem-solving. For example, students can apply computer game playing experience to their interactive story-writing exercise. Analysis objectives involve breaking complex information down into constituent parts, such as identifying the main elements of the story plot and specific character interrelationships. Synthesis objectives require the construction of something new by integrating several pieces of information, an integral part of any story-writing exercise. Finally, evaluation objectives are concerned with placing a value judgment on the data by comparing it with a given standard; e.g., comparing the traditional story writing experience with that of writing an interactive story.

Finally, it may take some training for students and teachers to take full advantage of some aspects of interactive stories. Most students wrote sequential stories, even though they were writing an interactive story that would not have to be "read" in the same sequential order by all readers. For example, we were told of a story that contained a plot that involved the completion of three quests. In a traditional story, the author would have described how the protagonist completed each of the quests in a particular order. In an interactive medium it would have been possible to write the story so that the three quests could have been completed in any order. However, the student storywriter required them to be in a linear order - this was probably due to experience with traditional linear stories. Students and teachers are so accustomed to traditional modes of expression that "thinking outside the traditional linear storywriting box" will take time and explicit effort.

6. Conclusion

We felt that our pilot storywriting

exercise was successful. We have learned that high school students are able

to create interactive stories using ScriptEase. We evaluated the effectiveness

of our tools and the tutorial material. In general, the students embraced our

tools and tutorials, although we did accumulate a series of ideas for minor

changes to both the tools and the tutorials. The teacher noted a distinct positive

change in attitude and behavior during the interactive storywriting exercise.

To test some of the hypotheses generated from our pilot and described in this

paper, we have planned a series of empirical studies, both with high school

students and university students. We are also interested in determining the

generality of our findings. For example, is interactive storywriting more engaging

over time or does the novelty factor play a large role? Is interactive storywriting

more engaging for all kinds of stories, for all learners of a particular age

or for people of all ages?

7. Acknowledgements

This research was supported

by grants from the (Canadian) Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Systems

(IRIS), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC),

Alberta's Informatics Circle of Research Excellence (iCORE), BioWare Corp.

and Electronic Arts (Canada) Ltd. We thank former ScriptEase team members James

Redford (M.Sc.), Dominique Parker (M.Sc.) and Sabrina Kratchmer (WISEST summer

student) for their efforts on ScriptEase. We also thank the anonymous referees

for suggestions that improved the manuscript and we especially thank our many

friends at BioWare for their feedback, support and encouragement, with special

thanks to Mark Brockington. Finally, we thank the students from the Grade 10

English class that participated in the pilot, not only for their great feedback,

but also for sharing their unbridled enthusiasm for interactive storywriting

with our team.

8. References

Bloom, B. S., Englehart,

M. B., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, O. R. (1956). Taxonomy of

educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1:

The cognitive domain. New York: Longman.

Ananny, M. (2002). Supporting children's collaborative authoring: Practicing written literacy while composing oral texts. In Proceedings of the Computer Supported Collaborative Learning Conference, Boulder, CO, pp. 595-596.

Gardner, H (1993). Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. New York: BasicBooks.

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Computers as Mindtools for schools: Engaging critical thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McFarlane, A., Sparrowhawk,

A., & Heald Y. (2002). Report on the educational use of games. Teachers

Evaluating Educational Multimedia Report. [Online]. Available:

http://www.teem.org.uk/publications/teem_gamesined_full.pdf

Robertson, J. (2001). The Effectiveness of a Virtual Environment as a Story Preparation Activity, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Robertson, J. & Good, J. (2005). Story Creation in Virtual Game Worlds. Communications of the ACM, 48(1), pp.61-65.

Santrock, J. W. (2001). Educational psychology. Toronto : McGraw-Hill.

ScriptEase (2005). Online.

http://www.cs.ualberta.ca/~script/scriptease.html

[Retrieved April 2005].

********** End of Document

**********