| 1. | Educational Problem | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | Conceptual Design | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Design Architecture | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. | Procedure | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. | Development | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. | Evaluation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. | References | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. | Acknowledgments |

| Appendix |

| Printer-friendly version |

![]()

Approaching Clinical Decision Making in Nursing Practice with Interactive Multimedia and Case-Based Reasoning

Som Naidu, The University of Melbourne

Mary Oliver, The University of Southern Queensland

Andy Koronios, The University of Southern Queensland

Abstract

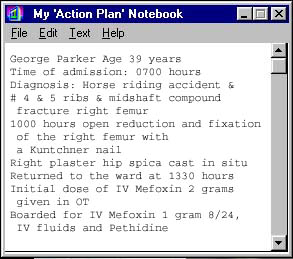

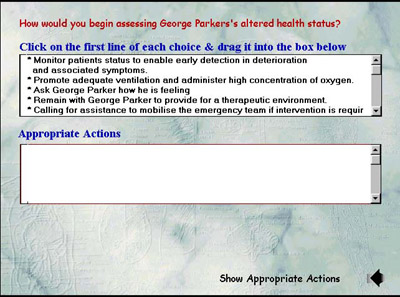

This paper describes the conceptual design,

development and formative evaluation of a self-paced multimedia learning

resource that is intended to facilitate clinical decision making in nursing

practice with case-based reasoning. With the help of a contrived situation,

the resource attempts to simulate the complexities of life in a typical

hospital ward, which places graduating nurses in the role of problem-solvers.

Problem solving in the simulation is based on a rich repertoire of cases

and stories that have been extracted from the experiences of expert practitioners.

This case-based reasoning architecture reflects a model of learning where

graduating nurses are coached in the development of decision-making skills

within the context of a contrived but an authentic problem. Formative

evaluation of this multimedia resource using structured and open-ended

question types has been carried out with individual and small groups of

practicing nurses. Their general impressions of this resource, and especially

its approach to learning, have been positive. More extensive evaluation

of the resource is currently in progress.

1. Educational

Problem

In much

of Australia (and very likely elsewhere), approaches to the preparation

of nursing students for a successful transition into the workplace has

been found to be ineffective. Recognizing that more of the same kind of

support was not going to be useful, we argued for a radical shift in helping

graduating nurses to make the transition into the workplace. Our proposition

combines powerful educational technologies and proven learning strategies

to build a self-paced technology-enhanced learning environment. Governments,

health care organisations and nurse educators have also suggested that

in order to prepare better nursing graduates for the challenges of the

workplace, there must be alternative ways of preparing graduating nurses

for the demands of clinical decision making in situ. An obvious

improvement would be increased collaboration between the employing organizations

and nursing education institutions to provide realistic learning situations

outside the formal classroom, and offered in a self-paced and self-instructional

environment. These alternative learning opportunities would need to be

solidly grounded in the authentic problems and situations of the nursesí

daily routines. The learning tasks would need to be immediately relevant

and meaningful to them, and not too removed from their workplace environment.